Library Study:

A Social History of the

Mechanics’ Institute Library of San Francisco

By

Cynthia Varady

San Jose State University

Professor Elizabeth Wrenn-Estes

LIBR 280-03

Table of Contents

Introduction

Early San Francisco: Yerba Buena 1776-1849

San Francisco: 1850-1853

The Beginning of Change

The Mercantile Library

The Mechanics’ Institute of San Francisco: The Beginning

A Home for a Library

The Struggle to Stay Alive

Birth of the Mechanics’ Industrial Fair

A Rivalry

An Expanding Economy

A Permanent Home

Women and the Institute

The Institute’s Founders

Andrew Smith Hallidie

California State University and the Mechanics’ Institute

Good-Bye to the Stockholders

San Francisco Gets a Free Public Library

Carnegie Libraries of San Francisco

A Merger between Rivals

The Great Fire

The Loss

Rebuilding the Institute Library

57 Post Street

Summary

References

End Notes and Works Consulted

The Mechanics’ Institute Library, located at 57 Post Street (Figure 1), is one of the oldest existing libraries and institutions of learning in the City of San Francisco. Originally established in 1854 as a reaction to the economic bust the newly founded city experienced at the end of the gold rush, the Mechanics’ Institute offered a venue for adult education and cultural improvement for a boomtown ravished by financial disaster (Mechanics’ Institute, 2009, para. 1).

Society of mid-19th-century America carried with it a belief in the nobility of the self-made scholar; those young men and women who took it upon themselves to further their education through reading and discussion. The emergence of the autodidact led to a rise in the construction of private, and later publicly funded libraries, many sponsored by Carnegie grants. The Mechanics’ Institute embodied the societal desire of working class people to improve upon themselves through education, and there was no better venue than 1850s San Francisco, where nearly half of the adult population found itself unemployed (Cohen, n.d. p. 263). However, the Mechanics’ Institute did not cater solely to the autodidacts of San Francisco; their mission was to further skilled trades through adult education, a prospect that was sorely lacking in California at this time. The Institute’s founders envisioned a library which would provide reference materials necessary to assist self-learners in their endeavors, and additionally supply an arena for intellectual debate, educational lectures, adult instruction and cultural improvement (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 22).

After 150 years, the Mechanics’ Institute has stayed true to its roots, remaining a beacon of enlightenment and intellectual expansion, offering lectures, book discussion groups, writing seminars, art exhibits and the oldest chess club on the west-coast to the citizens of the Bay Area.

In order to understand the history of the Mechanics’ Institute, it is necessary to examine the history of San Francisco, and the reasons a handful of the City’s population felt a cultural center such as this was vital to the enrichment and sustainability of this fledgling city. This paper will explore the intrinsic link between the Mechanics’ Institute and the City of San Francisco, placing the Institute in a historical context, examining the events which led up to the creation of this prominent Bay Area institution and the effect and influence the Institute had on the development of San Francisco as an industrial leader.

-Top-

Early San Francisco: Yerba Buena 1776-1849

In 1776, the Spanish empire began to extend north into the upper reaches of California. A team of priests, soldiers, and pioneers led by Gaspar de Portolà i Rovira[1] (1716–1784) (Figure 2), arrived on the shores of the Bay on October 31st 1769, after enduring a grueling 1,500 mile march from Mexico. Their objective was to create a religious and military outpost in the name of the King Charles III of Spain. These settlers christened their new home, Yerba Buena (Figure 3), meaning good herb, for the wild mint which grew on the surrounding hills (“Gaspar de Portolà,” 2010, para. 1; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 2).

The 1846 deployment of U.S. troops west into California and other Mexican settlements took the notice of the world. The belief in Manifest Destiny[2] rallied the young United States to expand its nation from sea board to sea board (“Manifest Destiny,” 2010, para. 1; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 2).

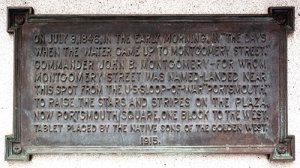

On July 18, 1846, Captain J.B. Montgomery (Figure 4) appointed his Spanish-speaking officer, Lieutenant Washington Allen Bartlett as California’s first American Alcalde[3]. This appointment was later ratified by a vote of the people (“California Historical Landmarks,” para. 4; “San Francisco Gold Rush, 1846-1849,” 2007, para. 13). On January 30, 1847, Bartlett renamed Yerba Buena, San Francisco (“San Francisco Gold Rush, 1846-1849,” 2007, para. 36).

The U.S. annexing of the California territory was quickly followed by another significant event in California history. On January 24, 1848 gold was discovered in Sutter’s Mill near Sacramento, setting off the California Gold Rush and subsequently, the greatest human migration the world has ever seen (Cohen, n.d. p. 263; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 2). To put this massive migration into perspective, San Francisco went from a city with a population of a few hundred in early 1848 to over 100,000 by December 1849 including 35,000 who came by sea, in addition to 3,000 sailors who abandoned their ships, and 42,000 who came over land (“Encyclopedia of San Francisco,” 2003, para. 17; “San Francisco Gold Rush, 1846-1849,” 2007, para. 158).

-Top-

The immense influx of adventure seekers and fortune hunters coming into California lasted for nearly two years, transforming the quaint Mexican village of Yerba Buena into the rowdy frontier City of San Francisco (Figure 5) (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 2). In May of 1850, Alcalde Bartlett was replaced by John White Geary (Figure 6), San Francisco’s first mayor. By July of 1850, the census bureau declared that the population of San Francisco was 94,766 (“San Francisco Gold Rush, 1850-1851,” 2007. para. 50). One year later, this number fell to roughly 30 thousand (“San Francisco Gold Rush, 1850-1851,” 2007, para. 130).

Soon the Gold Rushers were supplanted by a new wave of pioneers looking to strike their own fortunes. These newcomers were of the merchant and trade classes, selling supplies, building houses, running restaurants and hotels, opening bakeries and furniture stores, publishing news papers, and starting families. Brick and mortar buildings began to replace tents and provisional wooden structures. People started to converse as to the lack to schools, libraries, and other institutions of cultural enlightenment along with the lack of local industry and paying jobs (Reinhardt, 2005, pp. 2-3).

Much of the goods at this time were imported, and there was a general lack of a skilled labor force. These factors coupled with an unbalanced economy, isolation from support networks of the more established east coast, and the need of capital and industry, it was only a matter of time before the whole system began to breakdown (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 3).

Five years after the discovery of gold in California, the gold rush came to an end. Many for the former 49ers headed home, dispirited at not receiving their fortunes. The economic crash that followed saw the demise of Paige, Bacon & Company, a major banking-house in San Francisco. This fall was followed by an even more devastating collapse; the demise of leading express business, Adams and Company. The fall of these two giants created a domino effect, causing many smaller financial institutions to fail, as well as financially ruining many individual merchants (Paul, 1982, p. 8; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 3).

-Top-

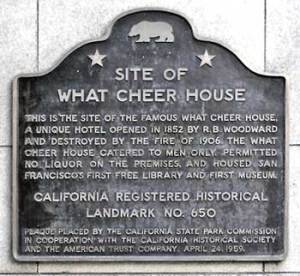

While the populations of disheveled and unruly Gold Rushers were busy getting on with their mission of striking it rich, a different element was taking root in the San Francisco. Still in its early stages of finding itself as a city, the first intellectual institutions began to form, starting in 1852 with the What Cheer House (Figure 7), San Francisco’s first free library and museum catering exclusively to men. In 1853 the City gained the California Academy of Natural Sciences (Figure 8), which was dedicated to collecting and documenting all biological life in California, and was one of the first institutions to provide employment to women in the fields of natural sciences. Also in 1853, the Mercantile Library Association of California, and the little remembered San Francisco Athenaeum Library Company, organized by and for African-Americans, both provided library needs to merchants of their respective classes. By 1854 the YMCA library had also formed for its membership (“Carnegie Libraries of California,” 2009, para. 1; “San Francisco Gold Rush, 1852-1854,” 2007, para. 63; “Encyclopedia of San Francisco,” 2003, para. 22; “Wall of Library Heroes,” 2003, para. 19). It would be another year before a half-dozen skilled craftsmen came together to establish their own association, this one focusing adult education and re-education, hoping to supply San Francisco with enough skilled builders and engineers to do away with the City’s dependency on imported goods. That same year, the Odd Fellows Library would also open its doors, offering library services to its constituency (“Carnegie Libraries of California,” 2009, para. 1).

However, from its beginnings, San Francisco attracted the literary elite inspired by its chronicles and the youthful, untamed atmosphere. The City became an important stop for young adventures seeking creative stimulation. A few of these exploratory young scribes came to stay – Mark Twain, Bret Harte, Ambrose Bierce, Joaquin Miller, and Ina Coolbirth were among the most notable genius that contributed to an array of San Francisco newspaper and journals (Wiley, 1996, p. 15).

-Top-

The Mercantile Library.

Occupying three rooms on the second floor of the California Exchange, amongst brothels and saloons, the Mercantile Library formed San Francisco’s first subscription library[4] by raising funds through the selling of shares (Figure 9). Modeled after the Mercantile Library of New York, the San Francisco association boasted the ability to grant moral and intellectual improvements to the young men of the City as an alternative to squandering their time and means on the idiocy and vices which carried such attraction to the inactive (Figure 10). In a city where just about anyone could consider himself a businessman, the offer for ethical and scholarly salvation found its niche (Wiley, 1996, p. 94).

The Mercantile Library founders were prominent members of the San Francisco business class which included traders of clothing, food, furniture, and building supplies – almost anything that could be imported. One of the main contributors to the establishment of the Mercantile Library’s was Brigadier General Ethan Allen Hitchcock (Figure 11)[5], who sold his personal library consisting of 2,500 volumes on philosophy, religion, and alchemy to the library for an unknown sum. The significance of Hitchcock’s contribution ensured the Mercantile Library a place as the City’s leading cultural institution (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 15).

-Top-

The Mechanics’ Institute of San Francisco: The Beginning

In December of 1854, a small group of civic-minded tradesmen, disappointed with the economic downturn and city’s dependence on imported goods, gathered to establish the San Francisco Mechanics’ Institute Library (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 22). The Institute was to be a club-like library and community center for adult education, with an additional focus on cultural and social activities (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 5).

Much like the Mercantile Library, the inspiration for the Mechanics’ Institute was a transplant from the East Coast, which in turn borrowed the idea from the English physician, George Birkbeck (1776-1841) (Figure 12)[6], founder of the first Mechanists’ Institute in 1821, the Edinburgh School of Arts, located in Scotland (Figure 13). Birbeck’s devotion and exuberance for adult education surpassed even his own expectation, and by 1841 there were over 300 mechanics’ institutes in Britain alone (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 7).

The Institute’s founders were skilled machinists, carpenters, and manufactures. Their common bond was a vision of transforming San Francisco into an industrial hub, along with their passionate distaste for imported merchandise, which they felt inflated prices and robbed locals of jobs and business prospects. The Mechanists’ Institute wanted to create a sustainable economy through the expansion of skilled trades. This ideology put them at odds with the merchants of the City and with those who had established the Mercantile Library (“San Francisco Mechanics’ Institute,” 2010, para. 9; Reinhardt, 2005, pp. 6-15).

The Mechanists’ Institute’s mission was simple; to kindle production on the West Coast, and in doing so, impassion the drive and sharpen the practical talents of their colleagues in order to contribute to the economic welfare of the City (“San Francisco Mechanics’ Institute,” 2010, para. 9; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 7). This mission was much more industrious than that of the Mercantile Library, whose focus was on moral and spiritual proliferation and less on the honing of hands-on skills.

The initial meeting of the Mechanics’ Institute was held on December 11, 1854 in the tax collector’s office at City Hall. Six men in total made an appearance and created an impromptu board. The meeting was led by George K. Gluyas, as contract carpenter, and Roderick Matheson (Figure 14), a stone mason, kept the minutes. Among other attendees were sawmill owner Benjamin Haywood; a blacksmith; and a commission merchant. Having decided on the Institute’s direction, the board went out to find donors, recruit members, and outline a constitution with educational principles patterned after Birbeck’s institutes, and design a subscription membership built on that of Benjamin Franklin’s Library Company of Philadelphia (Mechanics’ Institute, 1908, p. 21; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 7).

By the second meeting on March 29, 1855, several of the original group had been replaced. Five new officers and seven semi-permanent directors took over where the others had left off. Benjamin Haywood, one of the original attendees was elected president; John Sime, a building contractor, was appointed Vice President; John W. Brooks, an established manufacturer of stoves and hardware was voted treasure; William LaRoche, a coffee roaster and grinder, was given the position of corresponding secretary; and Peter Dexter became the new recording secretary. Dexter would later become the Institute’s first librarian (Mechanics’ Institute, 1908, p. 21; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 7).

From the start, the directors knew the type of library they wanted: open stacks with access to all books by all members. A game room, or at the very least, a section of the reading room where people could set up their chess boards and checker sets. The library would be open from ten to ten daily, with the exception of Sunday and major religious and national holidays. To finance their plans, the directors sold shares of the Institute at $25 a piece for voting membership, with a $3 due per quarter, or a non-voting membership for $5 with a $3 quarterly due (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 23; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 7).

However, in the dark days of the financial slump, many San Franciscans felt a $5 non-voting fee along with yearly dues amounting to $12 to be an outrageous sum of money. The $25 full-membership fee, which equated to approximately $500 by today’s standards, was out of reach of most of the City’s population (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 7).

The directors estimated it would take around 3000 voting members to fund the Institute, but recruiting proved harder than the Institute had bargained for. At the end of the first year, the directors had managed to recruit only 200 shareholders and a handful of non-voting members (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 7). This would be a tune heard frequently around the Institute for the next few years.

-Top-

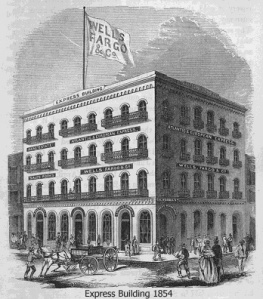

On June 21st, 1855, just half a year after the initial meeting of the Mechanists’ Institute, the directors rented a room on the fourth floor of the Express Building (Figure 15)for $25 a month. The building was located on Montgomery and California, and owned by Samuel Brannan (Kennedy and Kahn 1989, p. 20; Wood, 1930, p. 8). Two months prior on April, 5, board member, Sam Bugbee generously donated five books to the library from his personal collection. This contribution comprised the library’s total holdings. Bugbee selected the Bible; George Tichnor Curtis’s American Conveyances, a law text on the transference of property; a two-volume Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture; and a copy of the United States Constitution (Cohen, n.d., p. 269), and thus was the beginning of the Mechanic’s Institute Library and reading room. Soon after the library was opened, half of its collection was stolen; the liberated items were the Bible and the U.S. Constitution. Apparently these items warranted a closer examination than they could offer as reference materials. Fifteen days after Bungbee’s donation, the Honorable J.A. McDougall gifted thirty-nine volumes of U.S. documents and reports to the library (Kennedy, 1989, p. 20). By the end of the first year, the library contained 487 volumes and around $21 in cash (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 8; Wood, 1930, p. 8).

Contributing to the Institute’s rough financial start was the problem of poor lighting and the Express Building’s lack of elevator, discouraging members even further with the prospect of trudging up four flights of stairs to read by dim light. Unfortunately, candles too were an expensive luxury, though cheaper than gas lighting, and $2 was set aside from the already tight budget for the purchase of the necessary light source (Kennedy and Kahn 1989, p. 20).

With the Institute’s library slow but steady growth, a larger location was needed by its second year. However, their new home was no better than the first. With a rent increase of $40 and equipped with even poorer lighting than the Express Building, attendance plummeted, thrusting the Institute further into the poor house. The location was so unpopular no one bothered to photograph or say much more about it (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 8).

In July of the same year, Dexter, the librarian and secretary informed the board that his salary could no longer be afford by the fiscally strapped Institute, and he would from then on donate his time free of charge (Kennedy and Kahn 1989, p. 20).

-Top-

Although the Institute’s library holdings had grown to five hundred volumes by 1856, membership was still lacking and the accounts remained in the red. That was until an actress from North Carolina hosted a performance with proceeds benefiting the Institute. Julia Dean Hayne (Figure 16), the “toast of Charleston” arrived in San Francisco to hear of the struggling library and decided to perform her dramatic work, Madeleine, the Belle of Faubourg, on an evening in July, 1856 at the Metropolitan Theater. The $1,029 earned by Miss Haynes along with a few memberships with an annual fee of $1 kept the Institute afloat for another year while the directors scrambled to devise other means of generating revenue (Reinhardt, 2005, pp. 10-11; Wood, 1930, p. 8).

-Top-

Birth of the Mechanics’ Industrial Fair

By 1857, three years after they had begun, the Institute again faced closure. The gold supply had dwindled further along with it the revenue it produced. With the assistance of prominent businessmen, James Lick (Figure 17), Samuel Brannan (Figure 18) and Thomas O. Larkin (Figure 19), along with the Institute’s directors, most of whom were builders of different trades, devised a massive plan to raise the Institute out of debt while promoting California industry. Their idea was to construct a site for a local version of the industrial fairs previously held in London (1851) and New York (1853). Here, a yearly exposition would be held showcasing innovations in the field of engineering and agriculture. The hope was to encourage immigration to San Francisco, stimulate the economy, and drum up interest in the Institute in the form of voting members (Cohen, n.d., p. 266; Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 23; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 12).

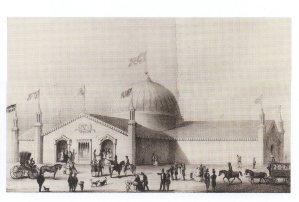

With 300 in cash and a plot of land donated by James Lick, located on the west side of Montgomery Street between Post and Sutter, the leaders of the Institute went to work raising funds through short-term loans and gifted materials. In total they managed to raise $7,000 (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 13; Wood, 1989, p. 9).

The first fair raised $2,784 in cash, and the pavilion (Figure 20) constructed for the event was valued at $3,500, which proved sturdy enough to serve as a lecture hall (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 13). The 1857 fair marked the first of 32 industrial fairs, each lasting three to six weeks every autumn, displaying products of California ingenuity and craftsmanship (Figure 21). All of the industrial fairs were profitable save for the third which incurred heavy financial loss, but by this time the Institute had established itself as the premier provider of adult education in California, offering scientific, mathematical, architectural and engineering classes along with a thriving technical library, and chess room to their members (Cohen, n.d., p. 266; Wood, 1930, p. 12).

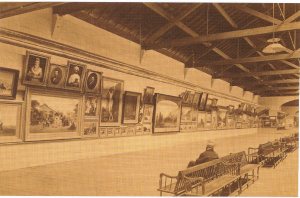

The Mechanics’ Industrial Fair became one of the premier social events of the City of San Francisco, attracting an average to 500,000 to 600,000 visitors from around the U.S. and the world. Products such as Levi-Strauss dungarees, Charles Krug and Beringer wines, Ghirardelli Chocolate, Singer Sewing machines, and Knaba pianos were just a few of the new and pioneering products unveiled at these fairs. However, the Institute didn’t limit their fairs to the fields of engineering and technology; fine art and music found their place among the exhibitions (Cohen, n.d., p. 267).

San Francisco didn’t attain its first art gallery until 1895 with the opening of the de Young. The fair provided a platform for their attendees to steep themselves in the work of local and international artists. Some notables which exhibited were William Keith, Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Hill, William Hahn, Charles and Arthur Nahl (Figure 22) (Cohen, n.d., p. 267).

Many came to witness new technologies, while others turned up to enjoy art and live bands, to boogie, gossip and flirt. The music and evening revelry drew large crowds of young people, many staying until the fair closed at midnight when an immense gong signaled an end to day’s festivities (Cohen, n.d., p. 267).

The mammoth success of the first industrial fair finally placed the Institute on the map and in the consciousness of San Francisco’s population (Hittell, 1898, p. 657). From its meek beginnings, the Institute could now begin to set into motion its initial mission of supplying adult education and technical library without the constant fear of economic failure.

In 1899, the fairs came to an end, having served their purpose in aided the development of Northern California’s industrial trades, making it no longer necessary to import skilled worker from the eastern sates and overseas (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 25).

-Top-

After the victory of the first Mechanics’ Institute industrial fair, the Mercantile Library found itself catering to mainly to those in the fields of business. With their monthly overhead running in the range of $600 their 472 members paying $1 every month in dues, the library was not making ends meet. After a year of heavy campaigning to gain more membership, the Mercantile Library still found itself with an overwhelming majority of members belonging to the merchant class (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 15).

With all efforts failing to diversify their patrons, Board President David Turner of the Mercantile Library announced his happiness and warmest wishes to the Mechanics Institute for having opened a library “for their own class” to enjoy and prosper from (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 15). In reality, this was the launch of a fifty year struggle for membership, rank and financial existence between the two subscription libraries in one very small and economically unsound city (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 15).

-Top-

With the extra income provided by the industrial fairs, the Institute was able to rent larger quarters on Montgomery Street between California and Pine. By this time, there were over 900 well used books in the library and attendance was high in the occupational classes as well as in the library. Income earned from the fairs was reinvested into the Institute for educational resources and library materials (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 23).

The 1859 discovery of silver in Nevada’s Virginia Mountain Range, know as the Comstock Load (Figure 23), boosted the economy of San Francisco (“Comstock Load,” 2010, para. 1). The City became the supplier of goods to both mines and towns of their eastern neighbor. This was an extremely prosperous era in San Francisco history. The local industry was booming and expansion of technological innovations was unmatched; Californians took out more patents than any other sate, most of which dealt with mining, agriculture, and milling machinery. Just as the founders of the Mechanics’ Institute has foreseen, San Francisco was becoming an industrial center, and the Institute adjusted their activities accordingly, offering more classes and expanding the library (Mechanics’ Institute, 1955, p. 15; Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 24).

In addition, the Civil War also stoked the flames of San Francisco’s growing economy, encouraging the further expansion of local industries. This expansion was due in part to a break in communications and trade with the eastern portion of the country because of the war. The period of prosperity was to last until the 1870s (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 23).

-Top-

The successes of the industrial fairs, flourishing library membership, and class attendance provided the Institute with the means for the purchase its first property in 1863; 529 California Street between Montgomery and Kearny (Figure 24). By this time, the library collection has amassed 5,000 volumes (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p, 24). Here the Institute was allowed to grow and prosper in a building all its own. However, in three years time, the Institute’s prosperity proved too great for the narrow Italianate street front building. The directors decided to have William Patton, the most successful architect in San Francisco at the time, design their new home. The location chosen was south of the City center on Post Street near Kearny. Here a three-story goliath of masonry and steel would be erected for the sum of $79,750 (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 24). It was planned that the street level would be rented to retail shops as a means of generating continuous income for the Institute, along with lecture halls for both classes and guest speakers, sitting rooms, and a dining hall. The second floor would house the opened stack library, the men’s and women’s reading rooms, the chess room, and two committee-meeting rooms. The third floor would contain additional areas for rent such as space for lodgers, scientific organizations or people in need of small offices. Despite constant complaints from members and staff as to the lack of space for the ever-growing library collection, the Institute would remain at the Post Street building for the next 30 years (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 24).

-Top-

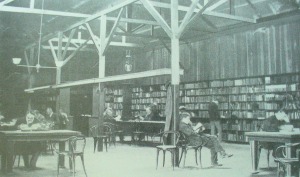

As to the question of treatment of women with regard to the Institute, no literature could be found that addressed the attendance by women to Institute classes, especially those of a mechanical or scientific nature. In the later years of the 1800s, the Institute began offering classes in figure painting and drawing (Figure 25), and it is possible that women were admitted to this type of instruction. However, women were granted access to the library (Figure 26) as a whole and were even provided with their own reading room.

From its first meeting in December of 1854 to its second in March of the following year, much of the original board had changed. The Institute’s first president, Haywood, a native of England and prosperous sawmill owner, sold off his holdings in Pennsylvania in 1850 and moved to Sonora, California and established the first sawmill in the state. He remained on the board of the Institute until moving back to Pennsylvania in 1855 (“Benjamin Haywood,” 2001, para. 1).

The original secretary, Scottish born Roderick Matheson, originally came to California in search of gold, but soon realized that striking it rich in the mines wasn’t as easy an endeavor as previously thought. After lasting only a short time in the mines, Matheson changed his sites to San Francisco, and worked on any project he felt would aid in improving the City at large. In 1852 he was appointed Comptroller of the City of San Francisco, and became an active member in one of the City’s many fire departments. Matheson eventually left San Francisco looking for a quiet and less dangerous location to raise his family, settling in Healdsburg, California (Clayborn, 2003, para. 6).

John Sime, the vice president of the second board in 1855 came to California in 1850. Three years later he tried his hand at politics, climbing the ranks to become a state assemblyman (Haas, 2009, para. 16). In addition to his political career, Sime was also owner of the successful finance company, John Sime & Co. (King, 1802, p.182), and was involved in California industry, with the purchase of the San Lorenzo Paper Mill in 1866 (Reedy & Reedy, 1967, para. 52). Sime served on the board of the Institute for one year (Mechanics’ Institute, 1908, p. 21).

Unfortunately, there is scant information to be found regarding the lives of George K. Gluyas (overseer of the first meeting in 1854), John W. Brooks (Treasurer, 1855), William LaRoche (Correspondence Secretary, 1855), and Peter Dexter (Recording Secretary 1855 and Librarian 1855-1865) (Mechanics’ Institute, 1908, pp. 21-23) outside of what has already been written here.

However, the most influential and well-known 19th-century leader of the Mechanics’ Institute can not go ignored; Andrew S. Hallidie (1836-1900). Hallidie resided as a trustee, vice president and president of the Institute, and was actively involved from its meager beginnings until his death (Mechanics’ Institute, 1908, p. 29; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 26).

-Top-

Andrew Smith Hallidie (Figure 27) was born Andrew Smith in London in 1836. He later took the name Hallidie after his godfather, Sir Andrew Hallidie. The son of engineer Andrew Smith, who held patents for the manufacturing of wire rope, Hallidie’s understanding and inventiveness in business and engineering, had an early start (“Andrew S. Hallidie,” 2009, para. 1).

In 1852 both father and son set sail for California were Hallidie’s father had a stake in some gold mines located in the town of Mariposa. The mines proved to be unsuccessful and Hallidie’s father returned home to England. However, Hallidie remained in California mining for gold, working as a surveyor, blacksmith and bridge builder (Andrew Smith Hallidie,” 2010, para. 3).

Hallidie gave up mining in 1857 and relocated to San Francisco. After ten years of building bridges throughout California and Nevada, he devoted his time to manufacturing wire rope. It was at this time that Hallidie invented the Hallidie Ropeway (Figure 28), an aerial mode of transporting mining ore through rocky terrain (“Andrew Smith Hallidie,” 2010, para. 5-8).

The success of the Hallidie Ropeway inspired Hallidie to take his idea underground in the form of uphill propulsion for street cars in San Francisco. Enlisting the help of important business men and engineers who had all worked previously together on establishing the Mechanics’ Institute, Hallidie was able to raise the capital necessary to begin construction on the Clay Street Cable Car (Figure 29) (Kahn, 1940, para. 30).

Hallidie’s intelligence sought the company of like-minded people, and as such, he was drawn to the Mechanics’ Institute. Hallidie, who became a trustee and vice president in 1864 and president from 1868-1878 and again in 1893-1895, has been given much credit for the success of the Institute (Kahn, 1940, para. 44).

It was through the efforts of Hallidie that the British Patent Office gifted the Institute’s library a full and complete set of British patents dating back to James I of England (1603-1625). It was Hallidie’s belief that libraries, through the compliment of reference materials such as patient reports, handbooks and manuals, could entice the natural yearning to learn in young men, setting them on the road to independence and self-fulfillment (Mood, 1946, p. 203).

-Top-

California State University and the Mechanics’ Institute

From the beginning, the U.S. had big plans for the academic future of its 31st state. Written into California’s constitution was a provision calling for the creation of a university that would contribute to the precious natural resources already found in the state, adding to the contentment and magnificence of upcoming generations. However, the center of education the founders pictured would take some twenty years to establish. (“19th-Century: Founding of UC’s Flagship Campus,” 2010, para. 1-2).

John W. Dwinelle, a San Francisco lawyer, had recently been elected state assemblyman by Alameda County with the aim of creating a university in the East Bay. The bill Dwinelle drafted was accepted by the legislature in 1868 and merged the College of California in Oakland, a struggling theological university, with the newly founded state land-grant institute, the Agricultural, Mining, and Mechanical Arts College, a non-secular institution offering degrees in agriculture, mechanics, mining and civil engineering. Combined, these two very different institutions formed the California State University (Figure 30), the first full-curriculum public university in California (Figure 31) (“19th-Century: Founding of UC’s Flagship Campus,” 2010, para. 2; Cohen, n.d., p. 265; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 25; “University of California, Berkeley,” 2010, para. 5).

To this institute of higher learning, the governor and both state senators would each appoint eight regents to direct the university. Supplementary to this number would be six ex-officio regents to include the governor; the lieutenant governor; the speaker of the assembly; the superintendent of public instruction; the head of the California Agricultural Society; and the president of the Mechanics’ Institute of San Francisco. For the next 106 years, the Mechanics’ Institute would take part in defining the programs of study for the University of California. Hallidie would serve as a regent for his 12 years as Institute president as well as by appointment of various governors from 1876 until his death in 1900 (Cohen, n.d., p. 265; Mechanics’ Institute, 1955, p. 15; Reinhardt, 2005, pp. 25-26).

Hallidie had lobbied to have the university’s campus built in San Francisco, and was saddened with the decision of rustic Berkeley as the new university grounds. He did however manage to have the Institute become the San Francisco campus for Berkeley’s College of Mechanics. This provided the Institute with the opportunity to access renowned faculty in the fields of science, history and literature, many of which gave free talks, filling the 500 seat lecture hall located in the expo pavilion (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 26).

-Top-

Hallidie wanted to ensure the positive impact the Institute was having on San Francisco continue indefinitely. With the future of the Institute in mind, Hallidie presented to the board a change in structure from that of a stockholders’ company into that of a nonprofit trust. The plan was to have the stockholders relinquish their ownership, making all members voters, and the board of directors would become trustees, transforming the Institute into a foundation with the advantage of receiving and pursuing charitable contributions. On December 8th, 1869, the Institute was reinstated with an arrangement insuring all earnings were endowed back into the organization. Ultimately, Hallidie’s restructuring of the Institute, coupled with the earnings generated from the industrial fairs, prevented the Institute from the doom faced by the Mercantile Library, which in time wasted away from want of public support (Mechanics’ Institute, 1955, p. 15; Reinhardt, 2008, p. 26; Wood, 1930, p. 13).

-Top-

San Francisco Gets a Free Public Library

By 1877, the lack of any sort of public library moved the residents of San Francisco to hold a meeting at Dashaway Hall (the local command center for the countrywide temperance and women’s suffrage movements) to discuss the issue. The meeting was instigated by Andrew Hallidie, who staunchly supported the funding and creation of a free public library for the citizens of San Francisco (Wiley, 1996, p. 10). Hallidie had just returned from touring libraries in other parts of the nation, and was appalled by San Francisco’s lack of free library services like those he had discovered in Massachusetts (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 46).

A year later, Governor William Irwin signed the Rogers Act (created by California State Senator, George H. Rogers, a good friend of Hallidie’s), which instituted a property tax in order to acquire library funding and establish a board of trustees. Under the Roger’s Act, several other California towns quickly went to work building their own public libraries, yet San Francisco lagged. The board of supervisors was unwilling to collect the tax from the citizens, so responsibility for initiating the library fell to the honorary trustees[7]. Working for free and without assistance, the trustees went forward to rent a provisional location, purchase materials, and employ a librarian (Albert Hart), spending roughly $14,000 out of their own pockets (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 47; Wiley, 1996, p. 98).

Another hitch in the plan for a public library was the lack of assistance and cooperation by the City’s superintendents in allowing the library to occupy any public building. The original plan was to place the library in the old City Hall in Portsmouth Plaza (Figure 32) after the offices had been relocated to the new building on Larkin and Market Streets, but this initial plan was later rejected by San Francisco supervisors. Finally the trustees managed to secure the second floor auditorium of the Pacific Hall on Bush Street between Dupont and Kearny (Figure 33). Shelving units were installed to hold some 5,000 books, most of which were bought on credit or donated. Many of the latter turned out to be in such poor condition they were unreadable. The initial usable collection was so sparse, circulation was suspended for fear that most of the items would be lost to thievery (Wiley, 1996, p. 10).

After everything was in order, the trustees set a date for the grand opening; on June 7, 1879 the San Francisco Public Library (SFPL) began service to the community (Wiley, 1996, p. 99). George Rogers, Andrew Hallidie, Henry George, and E.D. Sawyer addressed the crowd of men and women who filled the library, urging them to place pressure of their elected officials to support the library. The opening of the SFPL signaled the one year mark of the enactment of the property tax to fund it; however the City had yet to pay one cent to the SFPL or repay the trustees (Wiley, 1996, p. 102).

As for a building of its own, the SFPL would have to wait another thirty-seven years before a structure was erected specifically for its use. Architect George W. Kelham (Figure 34) designed the library in 1914 as part of the City’s rebuild project after the Great Fire of 1906. The City agreed and ground was broken for the main branch in 1915, and the corner-stone was laid the following year, some ten years after the 1906 disaster. By 1918 the branch was open to the public (Figure 35).

Despite its rough start, the SFPL was an instant hit with the people of San Francisco. Within days of its opening, tables in the reading room were so crowded people had difficulty finding empty seats (Wiley, 1996, p. 101). Another library in the City began to feel the pinch caused by the success of the SFPL; membership began to falter farther than every before for the struggling Mercantile Library (Cohen, n.d., p. 273).

-Top-

Carnegie Libraries of San Francisco

By the time San Francisco obtained Carnegie libraries, the City already contained a rich history concerning citizen involvement towards the creation of institutes of learning. However, none of these organizations were all-encompassing towards the public. The What Cheer House, although free to the public, only catered to men, while the rest of the list is made up of subscription libraries. The City was in need of a free library, open to all.

After the establishment of the SFPL in 1879, Mayor James Phelan (Figure 36) requested Carnegie funding for the establishment of further branches throughout the City. In June of that same year, San Francisco received $750,000 towards expanding the SFPL. However, the money was opposed by the San Francisco Labor Council who accused Carnegie of trying to dictate municipal policies under the guise of charity. Furthermore, Carnegie’s funding was not wanted because the Labor Council felt it was acquired by “questionable means” through the sale of supplies for warships at exorbitant prices to the U.S. government (Wiley, 1996, p. 111). Moreover, Carnegie’s behavior towards his workers during the 1892 strikes at his Homestead, Pennsylvania steel mill were not forgotten or forgiven (Wiley, 1996, p. 111).

Despite these hard feelings loudly heard from the Labor Council, the City supervisors voted to receive the grant. Being that the Carnegie gift was too low to build a new main branch facility, the City decided to create a $1.647 million bond measure and place it on the 1903 ballot. The measure passed, but later failed due to under-subscription (Wiley, 1996, p. 111).

The issue of underfunding would continue to plague the SFPL through the 1920s, whose city spent considerably less on its library that other West Coast towns. The City would receive another Carnegie grant to aid in the rebuilding of the branches which were lost in the 1906 fire, but city funding matching it would be to low to actually compleat the rebuilding projects (Wiley, 1996, p. 134). It would take twelve years for San Francisco to rebuild its main branch after the 1906 citywide devastation.

-Top-

A series of funding raising events in 1870 freed the Mercantile Library of debt for the first time in several years. These events also brought to light the troubles the library was suffering, and ultimately damaged the character of the library as an institution of learning and cultural honor. By the end of the 1870s, the Mercantile Library was in financial distress yet again (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 66).

The determination of a few tenacious individuals to keep the Mercantile Library afloat succeeded in doing so for the next twenty-six years, despite internal corruption[8], mismanagement, fiscal instability, and discord amongst the board of directors (Cohen, n.d., p. 274; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 67).

On January 2, 1906, after months of negotiations, the Mechanics’ Institute agreed to take on all the members of the Mercantile Library Association as life-time members, and to consolidate both institutions for a period of fifty years. The combined libraries would take on the name, “Mechanics’-Mercantile Library” (Figure 37). In 1955, at the end of this fifty year agreement, the Mechanics’ Institute dropped the mercantile portion and again became the Mechanics’ Library (Cohen, n.d., p. 274; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 67).

Originally, the merger was suggested between the SFPL and the Mercantile libraries. This would have required the SFPL to take on the Mercantile Library’s debt of $75,000, in addition the SFPL would have also absorbed the Mercantile’s collection of approximately 60,000 volumes, while also inheriting the Mercantile’s’ building. However, in the end, deciding that their clientele was more discerning than that of the SFPL’s, the Mercantile Library put the brakes on the deal, stating that the two classes of people would not mix well (Wiley, 1996, 106).

Just four months after the consolidation of the Mercantile and Mechanics’ libraries, tragedy would strike, destroying all the two institution has amasses over the last fifty or so years (Cohen, n.d., p. 275).

-Top-

At the beginning of 1906, the Mechanics’ Institute found itself wealthier that it had every thought possible (Wood, 1930, p. 15) – they had 4,150 members, more than ever before; the library contained 200,000 books plus collections of art, literature and rare editions which had previously been part of the Mercantile Library (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 25); through a series of successful industrial fairs and land deals they had amasses quite a savings (the selling of their California Street location for a profit of $75,000) (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 24); and their marriage with the California State University at Berkeley had raised their reputation and esteem beyond what the Institute had thought possible.

On April 18, 1906 at 5:12 in the morning, an earthquake registering between 7.7 to 8.3 rocked the City for close to a minute (“1906 San Francisco Earthquake,” 2010, para. 1; Ellsworth, 1990, para. 1). Shaking was felt up into Oregon and down into Los Angeles and inland all the way to Nevada, rupturing along the San Andres Fault for a total of 296 miles (Figure 38). The earthquake and resulting fire would be remembered as one of the worst natural disasters in the history of the United States. The death from both the fire and quake climbed to 3,000, with an estimate of $5 million in property damaged (1906 USD), and continues to be the worst natural disaster in California history. The fiscal impact has only recently been compared to that of Hurricane Katrina[9] which estimated $81 billion (USD 2005) in damages (“1906 San Francisco Earthquake,” 2010, para 1; Hurricane Katrina, 2010, para. 3; “Timeline of the San Francisco Earthquake,” n.d., para. 1).

The destruction brought about the earthquake and its aftershocks were felt throughout the City, but it was the fires (Figure 39) following the earthquake (over 30 individual burns) which produced about 90 percent of the property damage, destroying approximately 25,000 thousand buildings in 490 city blocks, leaving some 300,000 people without homes in a population of 410,000 (Figure 40). The initial fires were the cause of broken gas lines which jumped from rooftop to rooftop, spreading throughout the City. However a greater amount of damage was the result of inexperienced firefighters attempting to create firebreaks by demolishing building with dynamite. This action resulted in ruin of about 50 percent of the buildings which most likely would have survived. The fire burned for four days and was the seventh great fire to ravage San Francisco since the 1850s (“1906 San Francisco Earthquake,” 2010, para 10).

Shortly after the initial earthquake, Frederick M. Teggart[10], the Institute’s librarian, made his way to Post Street to find the library in ruins. All but one wall had collapsed. This solitary reminder of the building which had once graced Post Street proudly held the plaque dedicated to James Lick for his generosity to the Institute. In his will, Lick had endowed $10,000 to the Institute which used the funds to enlarge the library’s collection. This would be one of the few artifacts from the Institute to survive the “Ham-and-Eggs Fire”[11] which completely destroyed the building and its remaining contents. The plaque still hangs today in the Institute’s lobby at 57 Post Street (Figure 41) (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 25).

Joseph Cummings, secretary of the board of trustees, risking his life, made it to the library in time to remove records containing twenty-five years of board minuets; the ledger of members; some leases and contracts; and the original copy of the Institute’s constitution signed by the fist directors, from two safes located in the library’s basement. Cummings then placed the precious items in a safe deposit box of the Crocker National Bank (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 69).

On April 19, 1906, the day after the earthquake, a fire broke out in the Mechanics’ Pavilion which was being used as a makeshift hospital for those injured near City Hall by falling debris. Those seeking shelter in the pavilion were evacuated to Golden Gate Park at noon and by one that afternoon, the pavilion was engulfed in flames (Timeline of San Francisco Earthquake,” n.d., para 23). In addition to the Mechanics’ pavilion and library, City Hall, and two of the six SFPL branches were also lost in the fire (Wiley, 1996, p. 9).

-Top-

The destruction of the Mechanics’ Institute Library by the “Ham-and-Eggs Fire” took with it all 200,000 books (60,000 of which came from the Mercantile Library), the complete collection of British Patent records (which was so large it required an entire floor of the library), technical and scientific papers and documents, priceless California newspapers, and great treasures of literature and art. The only surviving records were those removed by Cummings to a safe deposit box in Crocker Savings Bank which protected them when that building too caught fire and burned to the ground (Cohen, n.d., p. 275).

-Top-

Rebuilding the Institute Library

Directly after seeing the ruin of the library a day before the “Ham-and-Eggs Fire” was to consume it, Teggart caught a ferry to his home in Berkeley and began work on refilling the library; sending telegrams and letters to libraries and book dealers in the Eastern part of the country, asking for assistance in any way possible. Teggart was instantly rewarded with a generous outpouring of 5,000 volumes donated by East Coast libraries and dealers (After the Gold Rush, n.d.). An informal meeting of half (7 of the 14) of the trustees granted Teggart permission to spent $5000 on new library materials. Teggart kept the replacement books in his home until a suitable location could be constructed in San Francisco. The main focus of the new collection was placed on architecture, construction, engineering, and just about anything else that would be useful in rebuilding the City (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 26; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 69-70).

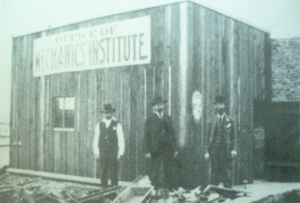

With so much of the City in ruin, building supplies were in high demand and in short supply. Provisional headquarters for the Institute were set up by May 23, 1906 in the empty lot where the pavilion once stood (Figure 42). The trustees went to work finding the location of as many of their members as possible in order to notify them of the Institute’s new address. This proved to be a difficult task since nearly one-third of their members had lost their homes or been killed in the catastrophe (Cohen, n.d., p. 276; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 70). By August of 1906, the Institute had lost close to 1,000 members. Many had relocated to areas outside the City, while others felt the temporary location inopportune (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 26). A temporary location for the library had been set up at 99 Grove Street (Figure 43). It was a simple yet effective one story wood and corrugated iron structure designed by Arthur Matthews[12] housed the chess and checkers club and the new book collection of nearly 40,000 volumes (Figure 44) (Cohen, n.d., p. 276; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 70).

While librarian Francis B. Graves (assistant librarian to Teggart who had left the library) bought, borrowed and begged for books, the trustees resumed their talks about the future of the Institute. They were all agreed that a new building was in order; however the debate lingered over where construction should take place (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 73).

Amid the bickering which ensued as to the future whereabouts of the Institute and library, two essentials were agreed upon; that the building should be large enough to house a fully functioning library with room to grow, and it should be equipped with the ability to generate additional income through rental space (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 73).

During those first few months of debate, Lewis Meade, the current Institute president, suggested the unthinkable; the abolishment of the chess club. The visceral response from the other trustees was such that Rudolph Taussig retook his former seat as president, and with words of reassurance that the chess club would remain a permanent fixture, set to work on hiring an architect and builders to being work at 57 Post Street (Reinhardt, 2005, p. 73).

-Top-

For the design of the new building, Albert Pissis (1852-1914) was chosen (Figure 45). Born in Mexico, Pissis and his family relocated to the U.S. when he was just six years old. Later, Pissis would be one of the first Americans to attend École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France in order to refine his skills in drawing. When Pissis returned to San Francisco in the 1880s, he brought with him the Beaux Arts style which was modeled after the classical era. Following the earthquake and fire, Pissis played a key role in the reconstruction efforts, and had a hand in designing many of the City’s landmark buildings[13] (“Albert Pissis” 2010, para. 1).

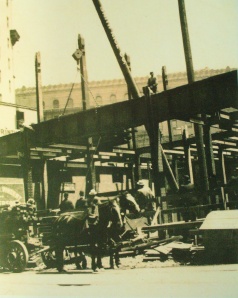

Pissis’s design for the Institute was a nine-story steel-framed, mixed-use building, faced with polished sandstone over a granite base, with a balanced, starkly classical façade. The street level would be rented as retail space, while the second and third floors would serve as open stacks to the library and offices. The fourth floor would house the Chess Club, and the remainder of the building would be rented as offices to outside businesses. The cost of construction was estimated at $250,000 (Mechanics’ Institute, 2009, para. 3).

Mostly local materials were used for the building, however a few standout pieces were imported such as white Manti sandstone from Utah for the façade; Oregon pine for both the lobby and the famous spiral staircase (Figure 46) and landings on the first and third floors, pink Tennessee and black Belgian marble for the lobby staircase walls. However, the backbone of the building, the iron framing and bookshelves were smelted and cast in California (Cohen, n.d., p. 275; Reinhardt, 2005, p. 74).

Construction began on June 4, 1906 (Figures 47 and 48), and by July 1910, the building was complete and the Institute moved in on July 15, 1910 (Figure 49). That same year, San Francisco voted to build a Civic Center so there would a venue for large gatherings and events. The City purchased from the Institute the site which had once held the Pavilion for the sum of $700,000, allowing the Institute to pay off their mortgage on 57 Post Street, and leaving them with a surplus of $51,228. At the 1914 annual meeting of trustees, the constitution was amended to where the accumulated assets of the Institute (the Post Street property, city bonds, etc.) be established as a perpetual endowment (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 26).

After the absorption of the Mercantile Library, the Institute library began to drift away from supplying strictly technical and scientific materials and began to carry items of a more general nature. The collection’s main focus was with finance and investments, social science, applied sciences, art and architecture, business management, fiction and literature, history, biography, music and chess (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 7).

By 1918, memberships had grown to 3,725 and the library resources number over 70,000 volumes. In 1923, the Chess Club moved to the fourth floor to make room for the ever-growing library collection (Mechanics’ Institute, 2010, p. 27).

-Top-

Despite its tumultuous and unsteady beginnings, economic downfalls and paramount disasters, San Francisco was a destination high-minded individuals flocked to, influencing and shaping a city of which they could be proud. These giants in the realm of intellect and imagination crafted a city that could hold its own against well established industrial centers, producing goods and skilled technicians in the mechanical and industrial arts to rival any existing metropolis in the U.S.

The Mechanics’ Institute Library wasn’t just a library and trade school; it was a pivotal player in shaping the City of San Francisco. Viewed by many as the only source of representation for the industrial arts, the Institute supplied a necessary element in keeping San Francisco abreast with the new innovations sweeping across the globe. The founders of the Mechanics’ Institute saw the potential San Francisco held, and created a center where that potential could flourish and grow. They accomplished this by providing a location where individuals, both men and women, could gain practical knowledge through accessing information available in the Institute’s library as well as through instruction in technical and artistic applications. In addition to providing these critical tools to the people of San Francisco, the Institute backed the establishment of other institutes of learning; by petitioning and assisting in the creation of a public library, and by sitting as ex-officio regents of the California State University at Berkeley. The Institute knew that in order for their city to keep pace with the rest of the world, they would have to produce San Franciscans who could contribute to scientific and technological advances, and they did just that.

The history of the Mechanics’ Institute Library is the history of San Francisco. It is impossible to look at one without examining the other. The handful of men who sat in the tax collectors office on that fateful evening in December of 1854 might have had no idea that their plan to begin the Institute would have influenced San Francisco’s future as greatly as it did, but without their efforts, San Francisco might have gone the route of many gold rush boomtowns; lost to history except for a few ramshackle storefronts and deserted mines.

-Top-

References and Works Consulted

1906 San Francisco Earthquake. (2010). Retrieved April 25, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1906_San_Francisco_earthquake

19th-century: Founding of the Flagship Campus. (2010). Retrieved April 24, 2010 from http://berkeley.edu/about/hist/foundations.shtml

Albert Pissis. (2010). Retrieved April 27, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Pissis

Andrew S. Hallidie. (2009). Retrieved April 21, 2010 from http://www.onlinenevada.org/Andrew_S._Hallidie

Benjamin Haywood. (2001). Edited Appletons Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 20, 2010 from http://famousamericans.net/benjaminhaywood/

California Historical Landmarks. (n.d.). Retrieved April 13, 2010 from http://www.noehill.com/sf/landmarks/cal0081.asp

Carnegie Libraries of California. (2009). Retrieved May 2, 2010 from http://www.carnegie-libraries.org/california/sf-main.html

Clayborn, H. (2003). Colonel Roderick N. Matheson: City Builder and Civil War Hero. Retrieved from http://www.ourhealdsburg.com/history/matheson.htm#2

Cohen, I.S. (n.d.) The mechanics’ institute library. In R. Wendorf (Ed.), America’s Membership Libraries (pp. 263-281). New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press.

Comstock Load. (2010). Retrieved April 27, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comstock_Lode

Ellsworth, W.L. (1990). Earthquake history, 1769-1989, chap. 6 in Wallace, R.E., ed., The San Andreas Fault System, California: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1515, p. 152-187. retrieved April 26, 2010 from http://earthquake.usgs.gov/regional/nca/1906/18april/index.php

Encyclopedia of California. (2007). Retrieved April 13, 2010 from http://www.sfhistoryencyclopedia.com/articles/timeline/index.html

Ethan A. Hitchcock. (2010). Retrieved April 20, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethan_A._Hitchcock_%28general%29

Frederick J. Teggart. (2010). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 21, 2010, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1350261/Frederick-J-Teggart

Gaspar de Portolà i Rovira. (2010). Retrieved April 13, 2010, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaspar_de_Portol%C3%A0

George Birbeck. (2010). Retrieved April 20, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Birkbeck

Haas, P. (2009). California: state assembly, 1850s. Retrieved from http://politicalgraveyard.com/geo/CA/ofc/asmbly1850s.html

Hittell, T.H. (1898). History of California, volume 3. San Francisco: N.J. Stone & Company. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=NUkOAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA657&lpg=PA657&dq=mechanics%27+institute+industrial+fair&source=bl&ots=Er6Dkos6aw&sig=_74H7iqA3sZY4FIV25QL7bh1odI&hl=en&ei=aubNS7D0Ko2uswPMqPWvDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CBMQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=mechanics%27%20institute%20industrial%20fair&f=false

Hurricane Katrina. (2010). Retrieved April 25, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hurricane_Katrina

Kahn, E.M. (1940). Andrew Smith Hallidie. Retrieved April 21, 2010 from http://www.sfmuseum.org/bio/hallidie.html

[Kennedy, L. & Kahn, E.M.] [1989]. Seven pioneer San Francisco libraries. San Francisco: Lawton Kennedy.

King, J.L. (1802). The history of the San Francisco stock and exchange board: by the chairman Joseph L. King. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=b-gJAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA182&lpg=PA182&dq=*John+Sime+%26+Co.+San+Francisco&source=bl&ots=e-vzaSWkWc&sig=kVcz9eMeh_tMYem6sAkPOaR0FjA&hl=en&ei=HYnOS_o1iPSyA5D97K4O&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CA8Q6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=*John%20Sime%20&f=false

Manifest Destiny. (2010). Retrieved April 20, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manifest_Destiny

Mechanics Institute. (2009). Retrieved February 13, 2010 from http://www.milibrary.org/

Mechanics’ Institute. (2009). Retrieved February 13, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Francisco_Mechanics%27_Institute

Mechanics’ Institute. (n.d.). After the gold rush: a 150-year photographic history of San Francisco’s mechanics’ institute. A Public Art Exhibit Guide.

Mechanics’ Institute, Library and Chess Room: Members Handbook. (2010). pp. 1-28.

Mechanics’ Institute (San Francisco, Calif.). (1908). Constitution of the mechanics’ institute of San Francisco, California, April 7th 1908. San Francisco, California: Press of Walter N. Brunt & Co. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=6X_AAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA21&lpg=PA21&dq=William+LaRoche+mechanics%27+institute&source=bl&ots=sRb4p7vkfH&sig=wfhretmE06Ch2mvFkZ4u8n7igKI&hl=en&ei=bkTPS8z9HYaAswOV6LCvDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=10&ved=0CCsQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=William%20LaRoche%20mechanics%27%20institute&f=false

Mechanics’ Institute (San Francisco, Calif.). (1955). 100 years of mechanics’ institute of San Francisco, 1855-1955. San Francisco, California: Mechanics’ Institutue.

Mood, F. (1946). Andrew S. Hallidie and librarianship in San Francisco: 1868-79. The Library Quarterly, 16(3), pp. 202-210. Retrieved March 21, 2010 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4303485

Paul, R.W. (1982). San Francisco after the gold rush. The Pacific Historical Review, 51(1), pp. 1-21. Retrieved April 15, 2010 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3639818

Reedy T.L., Reedy A.M. (1967). A history of the paradise park site. Retrieved from http://paradiseparkmasonicclub.com/cpw.shtml

Reinhardt, R. (2005). Four books, 300 dollars and a dream. Mechanics’ Institute: San Francisco.

Rubin, R.E. (2000). Foundations of library and information science. New York, New York: Neal-Shuman Publishing, Inc.

San Francisco Mechanics’ Institute. (2010). Retrieved April 23, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Francisco_Mechanics_Institute

San Francisco Gold Rush Chronology 1846-1849. (2007). The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco retrieved February 16, 2010 from http://www.sfmuseum.net/hist/chron1.html

Timeline of the San Francisco Earthquake: April 18-23, 1906.” (n.d.). Retrieved April 25, 2010 from http://www.sfmuseum.org/hist10/06timeline.html

University of California, Berkeley. (2010). Retrieved April 24, 2010 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_California,_Berkeley

Wall of Library Heroes. (2003). From the San Francisco Public Library. Retrieved May 2, 2010 from http://sfpl.org/index.php?pg=2000081701

Wiley, P.B. (1996). A free library in this city. San Francisco, USA: Weldon Own Inc.

[Wood, J.H.]. [1930]. Seventy-five years of history of the mechanics’ institute of San Francisco. Compiled by John H. Wood. San Francisco: The Institute.

-Top-

End Notes

[1]Gaspar de Portolà i Rovira was a Spanish army officer, governor of Baja and Alta California, explorer and founder of San Diego and Monterey.

[2] Manifest Destiny was a 19th-century idea that the United States was destined to spread its boarders from the Atlantic seaboard to the Pacific. This idea of destiny was used as a means of rationalizing the war with Mexico.

[3] Alcalde is a traditional Spanish municipal leader with both judicial and administrative duties. The transition from Alcalde to mayor in California takes place with Mayor with John W. Geary in 1850.

[4] Subscription libraries operated on a membership basis with fees paid towards gaining access to services, however members did not receive stockholder rights and were not considered owners in any sense (Rubin, 2000, p. 222).

[5] General Ethan Allen Hitchcock was a career U.S. army soldier. Known as the “Pen of the Army”, Hitchcock was an avid reader and published scholar. Hitchcock has amassed one of the largest collection of manuscripts on alchemy, most of which is now preserved in the Mercantile Library Association in St. Louis, Missouri.

[6] After giving a series of free lectures on the art of mechanics to groups of unskilled laborers, the questions George Birbeck received from his audience prompted him to begin a trade school for adult education.

[7] The Public Library Trustees consisted of Senator George H. Rogers; Andrew Hallidie; Irving M. Scott, the current president of the Mechanics’ Institute and general manager of the Union Iron Woks – the largest industry in the city of San Francisco; Andrew J. Moulder, a former state superintendent of public instruction; John S. Hager, a former U.S. senator; E.D. Sawyer, a retired judge; Robert S. Tobin, the secretary of the Hibernia Savings& Loan; Louis Sloss, a founding partner in the Alaska Commercial Company; John H. Wise, a lawyer; C.C. Terrill, a contractor; and Henry George, social critic and would-be tax reformer was in the position of treasure (Wiley, 1996, pp. 99-101).

[8] The Mercantile librarian was fired for embezzling $1300.

[9] Hurricane Katrina which hit the south-eastern United States is recorded as the fifth deadliest hurricane and the fifth strongest in U.S. history. 1,836 people lost their lives and property damages were estimated at $81 billion (“Hurricane Katrina,” 2010, para. 1 and 2).

[10] Frederick J. Teggart, the Institute’s seventh librarian from 1899-1907, and assisted in filling the shelves after the Great Fire of 1906. Born in Belfast, Ireland in 1870, Teggart emigrated to the U.S. in 1889. He attended Sanford University where he received his B.A. in English Literature in 1894. Thereafter he perused a career as a librarian at Sanford University, and then at the Institute. However, dissatisfied with librarianship, Teggart began lecturing at an extension of Sanford University in San Francisco in 1905. By 1911, Teggart was made an associate professor of history and curator of the prestigious Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, California (“Frederick J. Teggart,” 2010;).

[11] The “Ham-and-Eggs Fire” was the first of the 52 deadly fires to breakout in San Francisco following the 1906 earthquake. The fire began because a woman insisted on getting breakfast for her husband. The fire spread quickly due to a lack of water and roadblocks caused by fallen bricks and rubble from the surrounding buildings, limiting firefighters in their ability to move about the city.

[12] Arthur F. Mathews was an American Tonalist painter who was one of the founders of the American Arts and Craft Movement. Formally trained as an architect, Mathews and his wife Lucinda opened a furniture shop after the 1906 earthquake where he could showcase his talents in painting, craftsmanship and design (Arthur F. Matthews, 2010, para. 1-3).

[13] Pissis is best known for his designs of several Bay Area landmark buildings such as: Hibernia Bank (1892) building at Market and Jones streets; The Emporium (1896, rebuilt 1908) department store (originally called the “Parrot Building” and home of the California Supreme Court); James Flood Building (1904) at Market and Powell Street in San Francisco, California; Temple Sherith Israel (1904) in Pacific Heights. After the 1906 fire he built the White House Department Store (1908) (now Banana Republic store and White House Garage) at Grant and Sutter Streets; Mechanics’ Institute Library (1910).

-Top-